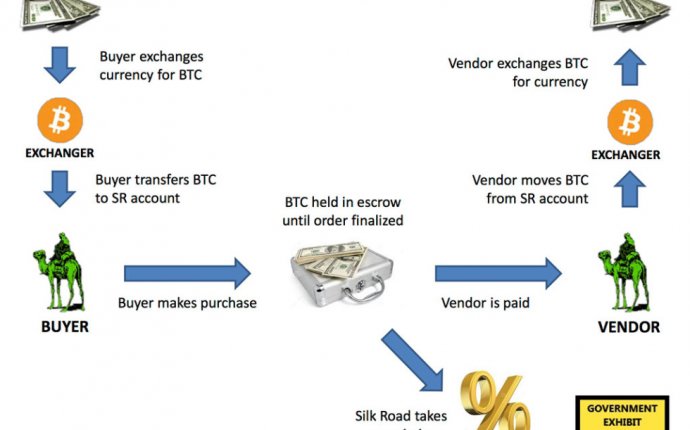

Using blockchain for Silk Road

Charlie Shrem sometimes describes himself as bitcoin's first felon. At the age of 22, he was arrested for his role helping people buy the digital currency, which was then used to buy illegal drugs on the website Silk Road. Shrem was released from federal prison last July. Keith Romer from our Planet Money team reports on what happened to Shrem in prison and what he's doing now.

KEITH ROMER, BYLINE: In 2012, Charlie Shrem was running a company called BitInstant that helped people trade dollars for bitcoins. It let a customer walk into Wal-Mart and buy bitcoins just like he or she would buy a money order. Charlie says business was good.

CHARLIE SHREM: We were processing over a million dollars a day.

ROMER: One of his biggest customers was a bitcoin broker on Silk Road, a website where people could use bitcoin to buy marijuana or cocaine or heroin.

Is there a moment that you remember when you were kind of like - oh, no, I've gone way too far down this road?

SHREM: Yeah, I do. And that was the moment they were placing the handcuffs on my hands.

ROMER: Charlie was arrested and eventually pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting the operation of an unlicensed money-transmitting business. He went away to prison. But even though he was locked up, Charlie stayed fascinated with the same thing he had been fascinated with on the outside - how people buy things.

SHREM: So the guy who fixes headphones only accepts protein bars. The guy who cuts your hair wants jars of peanut butter. But I would say the overwhelming majority of people would accept mackerel just because everyone else would accept it.

ROMER: Mackerel, like the fish. The packets of mackerel served as prison currency. But the mackerel could go bad, or someone could steal all your mackerel from under your bunk. And Charlie thought - what if mackerel could be more like bitcoin?

SHREM: And instead of people trading, like, individual mackerels between each other, they would be able to trade digitized mackerel.

ROMER: In Charlie's thought experiment, there would be no more storing of physical packets of fish. Inmates could just have an account that said how much digital mackerel they owned. Give a few inmates notebooks - they could stand in for the computers on the bitcoin network that keep track of all the transactions. In bitcoin parlance, the ledger in those notebooks would represent something called the blockchain.

Charlie never actually got to set up his whole digital mackerel experiment. Last July, he was released from prison. And he discovered that while he was locked up, bitcoin and blockchain had undergone this incredible transformation. All of a sudden, it wasn't just libertarians and drug dealers who were interested in it.

SHREM: Before I went to prison, there were no really - many blockchain products. It was only bitcoin. When I got out, that year was the year of the blockchain. That's when a lot of things happened.

ROMER: Social networking sites, logistics companies and a lot of the biggest banks in the world - they all wanted in. I spoke to Charley Cooper, the managing director of a company called R3. R3 is helping big banks set up their own private system based on the blockchain technology.

CHARLEY COOPER: We have nearly 80 members now from every continent on the planet.

ROMER: The technology that Charlie Shrem thought could be a way around the giant banks is now being co-opted by them. In the end, it's never the ideology behind the technology that determines how it will be used. It's what the technology is good for. Charlie Shrem, though, he's nothing if not adaptable. Last month, he launched his own blockchain company. It's got nothing to do with bitcoin.

For NPR News, I'm Keith Romer.

(SOUNDBITE OF EVOCATIV'S "THE LOVERS")

Copyright © 2017 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.