Total number of Bitcoins

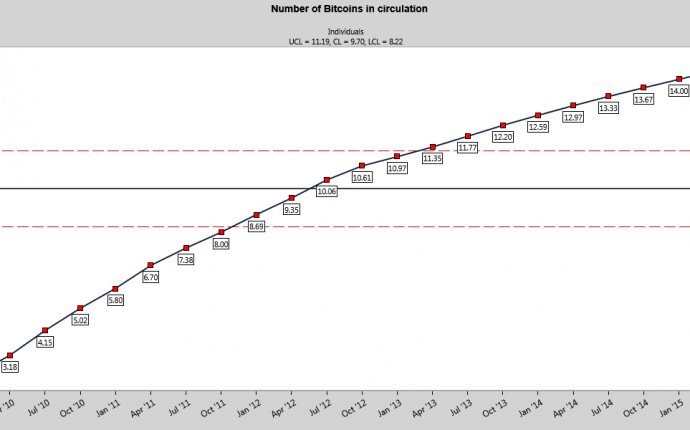

"Bitcoin" is the most widespread, cryptographically-secure Internet currency. It was created in 2009 by someone (or someones) who referred to themselves as "Satoshi Nakamoto." Once it was released into the wild, the bitcoin currency ecosystem operated on a public, inalterable schedule. We know exactly how many bitcoins there are in existence today (12, 446, 725) and how many there will eventually be in total: when the 21 millionth bitcoin is minted, the plates automatically self-destruct. (This is a metaphor, of course. There are no minting “plates, ” and nothing’s going to actually explode.) If you want to read the whole Wikipedia entry on bitcoin, have at it.

The genius of bitcoins is that they’re completely untraceable. Cash-money is anonymous and liquid, but even it has limitations—it must be used in face-to-face encounters; dollars have serial numbers on them, and if The Dark Knight is any guide, paper notes can be surreptitiously marked in many ways. But if cash is liquid, bitcoin is totally frictionless. As such, it is the first piece of computer technology to pose a fundamental challenge to the nation-state. That’s because the minting of legal tender is one of the base functions of government. And the person (or persons) who created bitcoin did so with the explicit goal of undermining the idea of sovereign governments.

For a while, a lot of people believed the gambit might work. Relatively speaking, there are very few places where you can use bitcoin as tender. But over the last year the value of bitcoins went on an extreme increase. In 2012, a bitcoin sold for about $10 USD. In January of 2013, the exchange rate began increasing, shooting up to $40. By December of 2013, a single bitcoin was selling for just over $1, 100. You read that right.

The bubble eventually popped and before last week the value of a bitcoin had collapsed to "only" about $600.

But bitcoin's problems are much more serious than a mere speculative bubble.

As of last week, bitcoin is probably functionally finished as a serious hope of ever achieving mass acceptance as a currency.

Because last week, someone stole half a billion dollars worth of bitcoins from Mt. Gox, the world’s oldest bitcoin exchange.

So here's what happened to bitcoin last week:

In order to buy bitcoins, you have to go to a bitcoin exchange—a place where you wire in funds from traditional currencies and they dispense bitcoins in return. It's kind of like a bank. The largest and oldest of these exchanges was a Japanese company called Mt. Gox. Please note the verb tense.

Several days ago, the tech rumor mills reported that Mt. Gox had a security problem. Some of their bitcoins, the rumors said, might have gone missing due to a vulnerability in their code. When Mt. Gox finally came clean to the public, it turned out that 750, 000 of its customers' bitcoins—and 100, 000 of their own—had been stolen. That's about $510 million worth. Or, to put it another way, about 7 percent of the entire bitcoin money supply.

Disappeared. All at once.

This past weekend, Mt. Gox filed for bankruptcy.

Bitcoin's evangelists keep pointing out that the exchange rate for bitcoins has held relatively stable post-Mt. Gox. And that’s true, so far as it goes. But it misses the real problems exposed by the heist.

Start with the bitcoin bubble. It formed because speculators were looking to get in on the ground floor of a new kind of currency that would eventually find mass appeal. The appeal of bitcoin was that, in a world where everything is quantified and collated and someone, somewhere, forever has an eye on you, bitcoin provided true anonymity.

Mind you, only some sorts of people really need anonymity—which is why bitcoin was the currency of preference on quasi-illegal exchanges such as Silk Road. But it wasn't much of a stretch to believe that, eventually, normal folks might want currency anonymity, too. (As Vanessa Redgrave coos in the criminally under-appreciated Mission: Impossible, "Anonymity is like a warm blanket.")

The only tradeoffs consumers would make in order to take advantage of bitcoin's privacy protections were (1) security and (2) acceptance. Which is to say, that the very anonymity of bitcoins made them very difficult to keep safe. And that bitcoins weren't (yet) accepted in all that many places.

The problem is that these two tradeoffs are inextricably linked. If the mass audience of consumers can't believe that their bitcoins are secure, then they won’t buy them. And if the mass audience doesn't buy bitcoins, then mainstream businesses won’t move to accept them.

The Mt. Gox implosion blows the lid off of the idea of bitcoin security. The problem isn't the theft—money gets stolen all the time. Banks are robbed every day. But people don't think twice about bank theft because whatever money of theirs is sitting in the bank is insured by the federal government. If a guy sticks up the Wells Fargo and steals the $1, 000 you just deposited, the FDIC makes everyone whole—and then armed agents of the state attempt to track down the robber and bring him to justice.

But there ain't no law in Deadwood. Which is to say, the Mt. Gox heist makes it plain that there's no FDIC for bitcoin. If your bitcoins get stolen, you're out of luck. What's more, if your bitcoins get stolen, the cops aren't going to go after the bad guys. In fact, it's not even clear that, if the bad guys confessed to the theft the next day that it would be possible to prosecute them.

And here's the thing: These downside risks aren't just a quirk of bitcoin being in its infancy—they're design features that will always be with the currency.

All of which is why I'm convinced that while bitcoin (or something like it) is likely to hang around as a niche commodity for certain kinds of gray- and black-market transactions (it offers something like the anonymity and compressibility of diamonds for the low-end crook), Mt. Gox pretty much assures that the average consumer will never use it. Because there is no way for you to ever ensure that your bitcoins are completely safe.

What the makers of bitcoin failed to appreciate is that sovereign currencies aren’t merely successful because they’re the product of monopolies. Governments give them all sorts of competitive advantages (the techies call them “network effects”) that non-state actors will never be able to match.