Blockchain Miners

AS THE bitcoin price continues to fall, sceptics have started to wonder what will happen to the industry underpinning this digital “crypto-currency”. Around the world, hundreds of thousands of specialised computers have been built to create (or “mine”) bitcoins and, in the process, validate transactions and protect the system. How does bitcoin mining work?

AS THE bitcoin price continues to fall, sceptics have started to wonder what will happen to the industry underpinning this digital “crypto-currency”. Around the world, hundreds of thousands of specialised computers have been built to create (or “mine”) bitcoins and, in the process, validate transactions and protect the system. How does bitcoin mining work?

The aim of bitcoin—as envisaged by Satoshi Nakamoto, its elusive creator—is to provide a way to exchange tokens of value online without having to rely on centralised intermediaries, such as banks. Instead the necessary record-keeping is decentralised into a “blockchain”, an ever-expanding ledger that holds the transaction history of all bitcoins in circulation, and lives on the thousands of machines on the bitcoin network. But if there is no central authority, who decides which transactions are valid and should be added to the blockchain? And how is it possible to ensure that the system cannot be gamed, for example by spending the same bitcoin twice? The answer is mining.

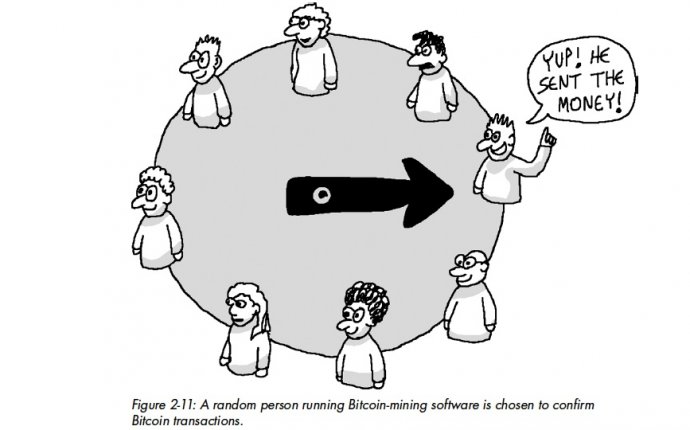

Every ten minutes or so mining computers collect a few hundred pending bitcoin transactions (a “block”) and turn them into a mathematical puzzle. The first miner to find the solution announces it to others on the network. The other miners then check whether the sender of the funds has the right to spend the money, and whether the solution to the puzzle is correct. If enough of them grant their approval, the block is cryptographically added to the ledger and the miners move on to the next set of transactions (hence the term “blockchain”). The miner who found the solution gets 25 bitcoins as a reward, but only after another 99 blocks have been added to the ledger. All this gives miners an incentive to participate in the system and validate transactions. Forcing miners to solve puzzles in order to add to the ledger provides protection: to double-spend a bitcoin, digital bank-robbers would need to rewrite the blockchain, and to do that they would have to control more than half of the network’s puzzle-solving capacity. Such a “51% attack” would be prohibitively expensive: bitcoin miners now have 13, 000 times more combined number-crunching power than the world’s 500 biggest supercomputers.

Clever though it is, the system has weaknesses. One is rapid consolidation. Most mining power today is provided by “pools”, big groups of miners who combine their computing power to increase the chance of winning a reward. As mining pools have got bigger, it no longer seems inconceivable that one of them might amass enough capacity to mount a 51% attack. Indeed, in June 2014 one pool, GHash.IO, had the bitcoin community running scared by briefly touching that level before some users voluntarily switched to other pools. As the bitcoin price continues to fall, consolidation could become more of a problem: some miners are giving up because the rewards of mining no longer cover the costs. Some worry that mining will become concentrated in a few countries where electricity is cheap, such as China, allowing a hostile government to seize control of bitcoin. Others predict that mining will end up as a monopoly—the exact opposite of the decentralised system that Mr Nakamoto set out to create.